For the most recently published information, please see our white paper: Addressing Target Company Privilege in Merger Agreements Five Years after Great Hill v. SIG

Abstract

An analysis of merger agreements closed since the Nov, 2013 Great Hill ruling reveals no apparent consensus on how selling companies are assigning rights of attorney-client privilege related to pre-closing communications. Some agreements are silent on the issue, while others variously assign the privilege to the target company shareholders as a group, to the shareholder group and their post-closing representative, or to the representative only. We analyze the frequency of these alternative formulations and discuss their pros and cons. Whichever approach is chosen, this is an important issue that should be considered by all selling companies in a merger and their shareholders.

Background

In most mergers, the buyer and the seller are each represented by legal counsel. The stockholders of the selling company often assume that communications with the law firm that “sat on their side of the table” in the negotiation phase of the transaction will continue to be confidential and unavailable to the buyer since it was the adverse party during the negotiation phase. That analysis, however, fails to take into account the actual nature of the attorney-client relationship. With most deals, the law firm’s client is the selling company, not its stockholders. At closing, the target company typically becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of the buyer. Therefore, there has been some question as to whether rights to the legal privilege and the attorney-client relationship flow to the buyer with respect to pre-closing communications.

In Great Hill Equity Partners IV, LP v. SIG Growth Equity Fund I, LLLP, C.A. No. 7906-CS (Del. Ch. Nov. 15, 2013), the Delaware Chancery Court addressed this issue and determined that the selling company’s attorney-client privilege related to pre-closing communications transferred to the buyer following closing. The court focused on the statutory language of Section 259 of the Delaware General Corporation Law, which says that following a merger, “all [of the target company’s] property, rights, privileges, powers and franchises, and all and every other interest shall be thereafter as effectually the property of the surviving or resulting corporation…” (emphasis added).

The court suggested that the target company could have avoided this outcome if desired by specifically excluding such privilege right from being transferred to the buyer in the contract language of the merger agreement.

New Data: A Comprehensive Analysis of Post-Ruling Merger Agreements

As Shareholder Representative on hundreds of private-target transactions annually, SRS Acquiom is uniquely positioned to assess whether and how selling companies are seeking to address the possible transfer of attorney-client privilege rights. We analyzed the merger agreements for over 50 transactions that closed since Great Hill was published.

No Apparent Consensus

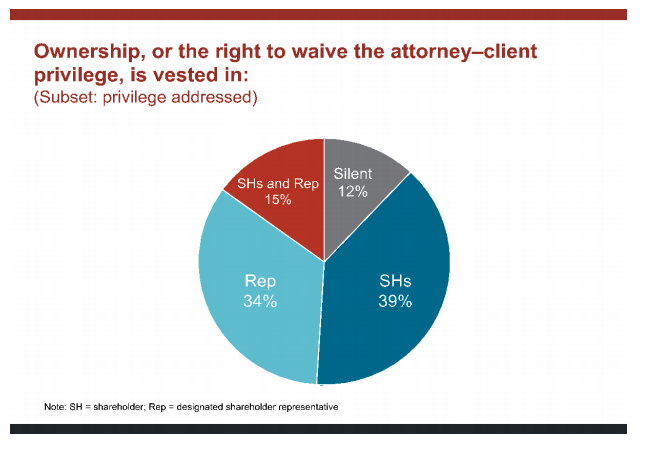

Since Great Hill, one-third of merger agreements still have no provisions addressing the issue.1 While the other two-thirds of transactions did include applicable language, as shown in the following chart, there is not consensus on what such a terms should say.

Over half of the agreements assign the privilege to the target company shareholders as a group or the shareholder group and their post-closing representative. We view any language assigning the privilege to a group as potentially problematic since it creates uncertainty regarding how it could later be affirmatively or accidentally waived, assigned or transferred and who would have the right to assert it. Other agreements assign the privilege to the representative only.

An example of privilege assignment language is below:

Buyer and the Company agree that, as to all communications between or among Firm and the Company, any of the Holders, the Shareholder Rep and/or any of their respective Affiliates relating to this Agreement or the transactions contemplated herein, the attorney-client privilege and the expectation of client confidence belongs to [the Shareholder Rep and the Holders/the Shareholder Rep/the Holders] and may be controlled by [such person, entity or group], and shall not pass to or be claimed by Buyer, Merger Sub, the Surviving Corporation, the Company or any Subsidiary or Affiliate of Buyer, the Surviving Corporation or the Company.

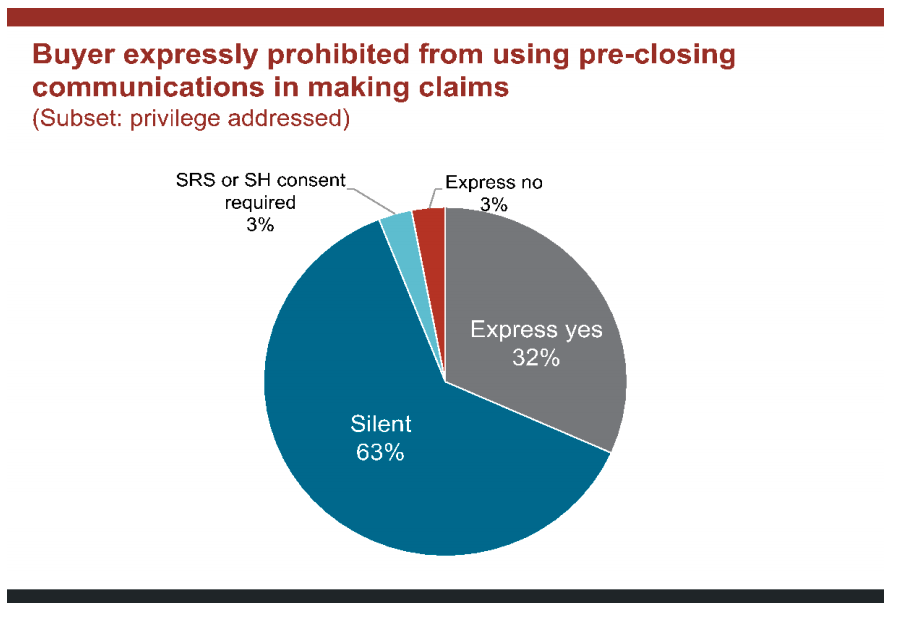

Another possible solution observed in a minority of agreements we analyzed is to limit what the buyer can do with such communications even if it acquires rights to them. This has the obvious drawback for the selling stockholders that the buyer would be able to see the contents of such communications but may be a solution if the parties either want the privilege to transfer to buyer or determine that there is no clear way to prevent such a transfer from happening. As shown in the chart below, roughly one-third of merger agreements have attempted to limit the buyer’s post-closing actions or behavior related to the privilege.

Such language could either be instead of or in addition to privilege assignment clauses. A provision limiting a buyer’s behavior may include something like the following:

Buyer agrees not to assert or use privileged communications for the purpose of asserting, prosecuting, or litigating any claim for losses against the Shareholders.

Since Great Hill did not give guidance on what approach may work best, there remains an issue as to which of these formulations may hold up to a future court challenge or attempted assertion of waiver. Because Great Hill essentially said, “add something” without specifying what that something should be, it leaves a number of other open issues, several of which are summarized below.

A. With transactions structured as mergers, how do the sellers retain the privilege?

When the transaction is structured as an asset purchase, assignment of privilege is relatively simple in most cases. The selling company remains an independent legal entity, and to make clear that the privilege is not transferred, it can be included in the list of assets specifically listed as “excluded assets” in the purchase agreement. In contrast, in a merger the target company typically becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of the buyer, meaning that under Great Hill the buyer would ordinarily acquire control of the privilege via its control of the target. Therefore, the privilege must somehow be transferred out of the surviving corporation and to another sell-side person or entity.

Such a transfer might not be as simple as the Great Hill court seems to imply. An attempted transfer to the target’s former stockholders would at a minimum leave open the question as to whether dozens or hundreds of separate individuals and entities would then each own – and be able to waive – that privilege. The target company may instead desire to have its privilege rights transferred upon closing to a single entity, such as a large stockholder or the post-closing stockholder representative. The Great Hill court did not address how such a transfer could be structured, but we believe it would be more complicated than simply stating in the merger agreement that a party other than the target company or buyer will hold the privilege upon and following closing. A court would have to accept how a new party came to hold the privilege and conclude that such a transfer was effective without itself constituting a waiver. At this time, we do not have clear guidance from any court as to how that analysis would be conducted.

B. Even if the privilege can be transferred, how do the sellers avoid an immediate waiver?

The Great Hill court noted that the target company did nothing to prevent the disclosure of the relevant communications to the buyer for over a year following closing. The court, however, did not address the issue of whether this would have constituted a waiver because it was not necessary to tackle that question once it had already concluded that the buyer owned the privilege following closing.

Therefore, the question remains that even if the target is successful in preventing the privilege from being transferred to the buyer, how can it prevent that privilege from immediately being waived? A waiver could be deemed to have occurred for a number of reasons.

First, the privilege could be deemed waived for the reason implied in Great Hill if the buyer obtains access to such communications following closing. Some agreements are now including language that says the buyer will not have access to such communications, but that probably is not accurate. While it might not have access to the attorney’s files, many communications will exist on servers or in files that the buyer will take over and could access intentionally or inadvertently. Since, in this scenario, a party that does not hold the privilege was able to access the contents of the related communications, a court could find that the applicable privilege has been waived. The parties could include language in the merger agreement similar to “clawback and non-waiver” provisions found in protective orders in the discovery context to try to prevent this. Such language would state that any post-closing access by the buyer to such communications will not waive or otherwise affect the rights of the selling stockholders or their representative with respect to the related privilege. Since Great Hill did not address that issue, it is unclear whether such a “privilege savings clause” would work. We note, however, that we do not see it included in many of the new clauses that are attempting to address this.

The following is an example of a privilege savings clause:

Buyer understands and agrees that any disclosure of information that may be confidential and/or subject to a claim of privilege will not prejudice or otherwise constitute a waiver of any claim of privilege. Buyer agrees to use reasonable best efforts to return promptly any inadvertently disclosed information to the appropriate Person upon becoming aware of its existence. Notwithstanding the foregoing, in the event that a dispute arises between Buyer, the Company or any of their affiliates and a third party other than a party to this Agreement after the Closing, the Company may assert the attorney-client privilege to prevent disclosure of confidential communications to such third party; provided, however, that to the extent such dispute relates in any way to this Agreement or the transactions contemplated hereby, the Company may not waive such privilege without the prior written consent of the Shareholder Representative.

Second, unless the courts accept a legal fiction that the target company and all its employees “forget” the privileged information upon transfer to an assignee, pushing them outside the zone of privilege by virtue of a transfer could function as a waiver. Therefore, even if the sellers are successful in preventing the buyer from ever obtaining any relevant communications, the fact that parties who no longer “own” the privilege have actual or constructive knowledge of the contents of such communications may still be deemed to cause a waiver of such privilege upon transfer.

Third, as noted above, if the privilege is assigned to a group, any member of the group could either affirmatively waive the privilege for reasons that might not be acceptable to other members of the group or inadvertently do so through its communications with others.

C. What is the scope of the communications that should be subject to any privilege retained by the sellers?

In Tekni-Plex, Inc. v. Meyner & Landis, 674 N.E.2d 663 (N.Y. 1996), the New York Court of Appeals ruled that privileged communications related to the merger transaction itself are retained by the sellers, but rights with respect to other attorney-client communications are transferred to the buyer. For instance, if the target company’s law firm had represented it over the years prior to the merger transaction with respect to other matters such as intellectual property or general litigation, the buyer would acquire all rights to all communications associated with those issues, but would not acquire rights to communications related to the merger transaction itself.

Merger parties that agree that the selling stockholders should retain privilege rights with respect to certain communications but not others might look to the Tekni-Plex ruling as a framework in defining which privileged communications would remain with the selling stockholders and their representative, and which would transfer to the buyer. One challenge with this construct is that there are some communications that would likely fall in a gray area. For instance, if the target asks its attorneys to do an analysis of third-party intellectual property rights because it wants to understand any risks to its operations, but that analysis also turns out to be relevant to what it includes in a disclosure schedule attached to the merger agreement, is that related to the merger or its general operations?

Therefore, even if the merger parties agree that privilege rights to pre-closing communications with counsel related to the merger will not be transferred to the buyer, the line as to what is intended to be included and excluded from that definition may be a little fuzzy.

To address this ambiguity, the merger parties might want to effectively quarantine the pre-closing communications that they intend to be carved out from being transferred to, or accessible by, the buyer. To do this, it may be necessary to set up communications systems that are separate from the target’s email and to specify in the merger agreement that all electronic and hard copies of such communications will be effectively walled off from other company systems and communications.2 The parties could couple this with a provision in the merger agreement in which the buyer and target covenant not to attempt to access any such communications following closing. This could have the effect that even if the privilege did flow to the buyer upon closing, such communications would be unavailable to it.

Looking Ahead

Our analysis of merger agreements since Great Hill reveal that new language is being included in merger agreements to address rights to the legal privilege and the attorney-client relationship with respect to pre-closing communications. No apparent consensus has emerged and the various solutions adopted have pros and cons. We will continue to monitor this issue and report on how the data on how it is addressed changes over time. One certain conclusion is that all selling companies should consider this often overlooked issue and how the merger agreement should address it.

The issues addressed in this article raise new and complex challenges that require sophisticated legal analysis on each transaction. Prior to entering into any such transaction, you should consult with experienced legal counsel.

Footnotes

1 See Great Hill Drafting: Ownership of Attorney-Client Privilege of Pre-Closing Communications, https://info.srsacquiom.com/Great-Hill-Drafting, (July 2016)

2The parties could also consider destroying all such communications, but that could create a host of

additional risks and issues for the law firm and the target entity.

Paul Koenig

Chief Executive Officer tel:303-957-2850

Paul is the chief executive officer and co-founder of SRS Acquiom.

Before co-founding SRS Acquiom, Paul was one of the founding partners of Koenig & Oelsner, a Denver-based corporate and business law firm with a strong practice in mergers and acquisitions, securities, and financing transactions. Prior to that, he was an attorney in the Chicago office of Latham & Watkins, and in the Colorado office of Cooley LLP.

Paul has authored numerous articles and is a frequent speaker at industry events. He received his BBA in finance from the University of Iowa and graduated from Northwestern University School of Law.