With the cessation of LIBOR behind the financial markets, the SRS Acquiom Loan Agency team looks back at the final transition away from the lending benchmark. We provide a glimpse into the current state of the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) and the implementation of alternative benchmark rates on both legacy and new institutional loans. The process has been widely regarded as a successful transformation in the financial industry.

Farewell LIBOR

The cessation of LIBOR after nearly 50 years as a global lending benchmark rate is paving a path to a more reliable and transparent system of benchmarking for the financial markets. The nearly decade-long initiative to transition from LIBOR, the primary rate that banks charged customers to borrow cash that had been used since the 1980s, effectively concluded at the end of June. The elimination of the benchmark did not come without skepticism of an innocuous changeover. Yet, the ultimate shift proved mostly orderly.

“The transition from LIBOR to risk-free rates is a monumental milestone for the financial markets,” James von Moltke, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Financial Officer said in a July 3 company statement.

LIBOR History

After the 2008 financial crisis, some LIBOR rate-setting banks were accused of manipulating the benchmark to benefit their bottom lines. LIBOR suffered nearly a decade of negative headlines and misconduct. In 2014 the Federal Reserve commissioned the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (ARRC) to select a replacement benchmark rate for LIBOR.

The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), a dollar-denominated stable interest rate benchmark that is not subject to the vulnerabilities of LIBOR, emerged as the preferred solution in 2017. SOFR is a data-driven rate based on the overnight U.S. Treasury repo rate. It is regulated by the Federal Reserve Board and Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). An expiration date of June 30, 2023, was set for LIBOR.

A Look at Alternative Rates

As discussions prevailed, credit-sensitive rates such as Ameribor and Bloomberg Short Term Bank Yield (BSBY) emerged as alternatives to the risk-free SOFR rate. Market demand also prompted development of Term SOFR, a rate emulating the one-, three-, six- and 12-month borrowing tenors previously available under LIBOR.

Lenders were urged to proactively transition away from LIBOR ahead of the deadline by refinancing loans into a SOFR rate, which is determined by more than $1 trillion of daily repo transactions.

New loans began pricing over SOFR at the beginning of 2022. Most loans transitioning from LIBOR to SOFR did so with a credit-spread adjustment (CSA) to account for historical differences between a credit-sensitive rate (LIBOR) and a risk-free rate (SOFR). While there is no standardized CSA, four options emerged as possibilities: no CSA, a flat 10 basis points, 10 basis points for one-month, 15 basis points for three-month and 25 basis points for six-month rates, and finally, ARRC’s recommended adjustments of 11 basis points for a one-month rate, 26 basis points for a three-month rate and 43 basis points for a six-month rate. ARRC’s structure has been unofficially accepted as “market standard” and is based upon the five-year historical difference between one-month LIBOR and one-month SOFR compounded in arrears.

Nevertheless, the topic of CSAs has been somewhat contentious. As LIBOR and SOFR diverged, borrowers questioned the need for CSAs, and about 65% of new deals do not explicitly quote a CSA but rather have it embedded in the rate calculation. Some new-issue loans have cleared without a CSA. However, among those loans that have gone through the amendment process, nearly all required a CSA to address the mismatch in base rates.

The Divergence of Term SOFR and SOFR: Borrower Beware

Term SOFR is derived by looking at where futures contracts tied to SOFR trade compared with current SOFR rates thereby reflecting what SOFR may average over a period of one-, three-, six-, and 12-month terms. Over an extended period of time, Term SOFR should be consistent with actual daily spot SOFR rates. However, over shorter terms SOFR rates may diverge from the expectations driven Term SOFR should repo rates change unexpectedly.

Periods of divergence can occur when the U.S. Federal Reserve hikes, cuts, or holds the Fed funds rate in a manner inconsistent with market consensus and could potentially be a detriment to borrowers. If the Fed unexpectedly cuts rates, actual daily SOFR rates will quickly fall and likely adjust faster than the Term SOFR rate used at the start of the loan interest period resulting in borrowers payinga higher interest rate than expected. Yet, should the reverse occur and actual spot SOFR rises quickly compared with projections for Term SOFR, borrowers will pay a lower interest rate than expected.

SOFR: So Far So Good

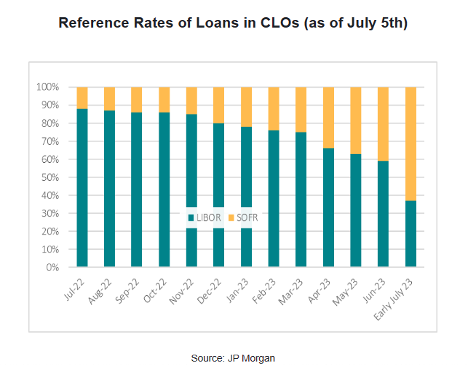

Many loan market participants were amending loan contracts to facilitate a smooth exit from LIBOR ahead of the cessation date. Roughly half the $1.4 trillion loan market switched to paying interest tied to SOFR prior to the June 30 deadline, according to JPMorgan Chase. Most companies that elected to preemptively switch chose either a version of SOFR, BSBY, or American Financial Exchange’s Ameribor.

Many of the remaining loans that did not switch in advance of the deadline were to automatically switch into the SOFR rate per fallback clauses in loan documentation. The timing for fallbacks depends upon specific language in a loan agreement and, as such, final transitioning to SOFR will likely continue for the remainder of this year. Thus, the fallback language does not immediately convert a loan contract to SOFR but will require a loan to run out its existing LIBOR interest period and then shift to a SOFR reference rate upon the next interest rate determination. Where there is not a clearly defined replacement benchmark rate in the loan documentation, Congress enacted the LIBOR Act to address transactions that had no LIBOR transition provisions.

Simplifying Via Synthetic LIBOR

Nearly 8%, or $100 billion of loans (“legacy loans”), did not provide for fallback language and were unable to refinance their debt from a LIBOR-based rate to a SOFR reference in time, according to research by Covenant Review. For legacy contracts with no ability to fallback, the Ice Benchmark Administration announced in April it would publish an unrepresentative “synthetic USD LIBOR’ through September 2024.

Synthetic USD LIBOR will be Term SOFR plus the ARRC recommended CSAs. So the same rate will be used in loans with ARRC hardwired fallbacks as well as those subject to the Adjustable Interest Rate (LIBOR) Act, which will replace LIBOR with one-month Term SOFR. In the U.S., synthetic LIBOR might be used for those loans that have no fallback language in their contract and would otherwise go to Prime (which is roughly 3% higher than SOFR) and or those loans with amendment fallback language that have no direct or indirect “non-representativeness” transition triggers. Synthetic LIBOR essentially serves as a safety net and will ease the transition for legacy contracts without the fallback language. After September 2024, publication of synthetic LIBOR rates will permanently cease. It may not be used in new contracts.

Synthetic LIBOR is not without downside. According to Mark Mauer, Wall Street Journal, companies could “trip their debt covenants and face technical default if their hedging and financing fall back to different benchmarks,” such as synthetic LIBOR for one and certain versions of SOFR for the other. Companies with no changeover language as well as those with fallback clauses in their loan documentation may roll over existing LIBOR-based loans using synthetic LIBOR for as long as 12 months before the phaseout. Prolonging the transition could potentially create further headaches for companies.

Hedging Challenges

Hedging has long been a practice for traders to minimize risk exposures by offsetting a position in one asset that will lose in value with one that will gain in value. As advised by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARCC) counterparties are only allowed to enter into a Term SOFR swap if they are hedging an existing position in Term SOFR or using the benchmark to exit from a legacy LIBOR exposure. A ban on interdealer transactions in Term SOFR has left some dealers concerned about basis risk, and trading restrictions under Term SOFR rules may limit liquidity in hedging and derivates trading, causing banks to hold higher levels of risk on their books and limiting their ability to lend.

Future of Lending: IOSCO's Evaluation of LIBOR Alternatives and the Implications for Market Integrity

The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) assessed implementation of four possible replacement benchmarks for LIBOR. Two term-SOFR rates—CME and IBA, “fell short of SOFR,” according to IOSCO’s July 3 published review. These Term SOFR rates are deemed “suitable for limited use” as they rely on a deep, liquid derivatives market that is based on SOFR. Still, Term SOFR is effectively the U.S. lending benchmark for new and legacy business loan contracts, according to the LSTA.

Furthermore, IOSCO concluded that the Ameribor and BSBY benchmark rates, both of which are credit-sensitive rates (CSRs) are subject to similar vulnerabilities of LIBOR, and ultimately may “threaten” market integrity and financial stability due to liquidity risks. The Financial Conduct Authority has repeatedly negatively viewed any transition to so-called CSRs, as they have the potential to reintroduce risks associated with LIBOR.

With the transition largely behind the market, there concern is for those loans pegged to CSRs such as BSBY and Ameribor. IOSCO recommends the use of CSRs not be viewed as IOSCO-compliant. Still, CSRs may be offered, at the discretion of borrowers. Nevertheless, market participants didn’t let the transition stand in their way of business, and they continue to operate as normal with regard to the new lending-rate options. It will be interesting to see how these alternative rates play out in the market over time and in the post-LIBOR landscape.

The SRS Acquiom loan agency team is prepared to discuss further context regarding SOFR and alternative rates in existing and new credit agreements. Please reach out with any questions or for additional insight.

Term SOFR is derived by looking at where futures contracts tied to SOFR trade compared with current SOFR rates thereby reflecting what SOFR may average over a period of one-, three-, six-, and 12-month terms. Over an extended period of time, Term SOFR should be consistent with actual daily spot SOFR rates. However, over shorter terms SOFR rates may diverge from expectations of Term SOFR should repo rates change unexpectedly.

These periods of divergence may occur when the U.S. Federal Reserve hikes, cuts or holds the fed funds rate in a manner not consistent with market consensus and could potentially be a detriment to borrowers. If the Fed unexpectedly cuts rates, actual daily SOFR rates will quickly fall and adjust faster than the Term SOFR rate used at the start of the loan interest period. The borrower will have paid a higher interest rate than realized. Yet, should the reverse occur and actual spot SOFR rises compared with projections for Term SOFR, the borrower will have paid an interest rate based on expectations for SOFR that were lower than realized.

Renee Kuhl

Managing Director, Loan Agency tel:612-509-2323

Renee is the managing director of the SRS Acquiom Loan Agency Group. With more than 15 years of experience as administrative and collateral agent on loan transactions and more than ten years managing teams in loan agency and restructuring products, she is an accomplished financial industry professional and leads the loan agency business globally.

Before joining SRS Acquiom, Renee served as an administrative vice president at Wilmington Trust, N.A., most recently leading the loan agency and restructuring products. In addition to her 10 years at Wilmington Trust, she also worked for Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. in the corporate trust and shareholder services departments.

Renee has a Juris Doctorate from Mitchell Hamline School of Law in Minnesota, and a B.A. in political science and history from Azusa Pacific University in Azusa, California.